Dealing with the Devils: Examining Duke’s dominant two-way performance against Baylor

Khaman Maluach closes off the rim, Patrick Ngongba steps into an expanded role, Cooper Flagg ignites secondary action, plus how Duke picked at Baylor's switch scheme

The Baylor Bears bookend the 2024-25 season with the program's two least efficient defensive performances since the 2007-08 season. On Nov. 4, Gonzaga dropped 101 points on Baylor, resulting in a defensive rating of 1.44 points allowed per possession. In the Round of 32 in Raleigh, Duke shot 12-of-22 from beyond the arc (54.5 3P%), posted a 17-to-6 assist-to-turnover ratio, and scored a staggering 1.50 points per possession. This marked the third time this season that Duke scored at least 1.50 points per possession — joining the February wins over Stanford and Illinois — but it also represented the least efficient defensive performance for Scott Drew's team in at least the last 18 seasons.

With a finish outside the Top 60 nationally in adjusted efficiency, this is not a typical Baylor defense. However, the two-way performance from Jon Scheyer’s team was notable, as Duke hovered above Baylor’s attempts to drag the game into the mud, propelling the Blue Devils back to the Sweet 16 for a rematch with Arizona.

Quick plug: Before we dive deeper into Duke’s performance against Baylor, here are two analysis pieces following Duke’s November win in Tucson. While much has changed over the past few months — with both teams dealing with injuries and altered rotations — there’s still valuable insight to be gained.

Now, let’s delve into Duke’s dominant win over Baylor, staring with the defense.

Got the drop

Baylor's offense this season was built around spread pick-and-rolls with guards VJ Edgecombe, Robert Wright and Jeremy Roach as the primary ball handlers, along with 5-out actions initiated by center Norchad Omier. The screen-roll foundation produced a lot of off-dribble shot attempts, resulting in Baylor’s lowest assist rate (52.8 percent) in over a decade. According to CBB Analytics, 51 percent of Baylor’s field goal attempts this season came from the paint, while another 40 percent of their field goals came from beyond the arc. Baylor assisted on only 47.1 percent of its 2-point field goals this season, ranking in the sixth percentile nationally.

The drives created slash-and-kick opportunities, with Wright leading the team by assisting 2.1 three-pointers per game. As a team, Baylor made 281 three-pointers this season, 84.5% of which were assisted. This offense focused on running its actions and attacking the paint, with Omier rolling to the rim while floor spacers Jayden Nunn (41.5 3P%), Jalen Celestine (34.5 3P%) and Langston Love (31.3 3P%) spread the floor for kick-outs.

Entering the game, Duke’s defensive approach was to take those looks away, or at the least make it tougher to access those go-to areas on the floor. The defensive template for this matchup included a lot of drop coverage with Duke’s centers — Khaman Maluach and Patrick Ngongba — defending below the level against Baylor’s spread ball screen offense.

In this alignment, the 5 (Maluach) starts a few feet below the level of the screen and then sinks further into the paint as the ball handler drives toward it. The on-ball defender — Tyrese Proctor, in this case — fights over the top of the screen, pursuing the ball handler from behind.

Duke’s weak-side defenders helped packed the paint, too — sliding into the lane as Baylor’s center rolls to the rim. There isn’t much space for Omier to roll into with Sion James and Mason Gillis collapsing the lane, nor is there room for Roach to squeeze in a pocket pass. The presence and activity of Maluach in the middle ground helps contain both Omier and Roach, buying Proctor time to recover and bother his former teammate, who settles for a tough off-dribble 2-point attempt.

On this 5-out possession for Baylor, Omier initiates a handoff action with Love in the left slot. As Love turns the corner, Maluach drops into the paint while James fights over the screen. Kon Knueppel helps off of Roach, providing support at the nail. Cooper Flagg sinks off Wright on the left wing. As Love and Omier attempt to run the screen-roll, notice the congestion in the paint — Duke has it packed in.

Three Duke defenders have at least one foot in the paint, and two — Maluach and James — are literally guarding Omier with a hand on him. Love is forced to settle for a tough runner from between the free-throw line and the restricted area. This is an inefficient attempt and exactly the type of shot the Blue Devils wanted to force.

One twist Duke added to this drop coverage approach was a late switch on certain possessions. Specifically, Maluach and Ngongba would begin in drop coverage and remain in that position for a dribble or two with the ball handler. Once the Baylor guard neared the paint or extended the play long enough, Duke’s centers would switch out, while the guard would switch onto Omier as he dove. This tactic allowed Duke to keep the ball in front, prevent the dive to Omier and avoid getting caught in rotation.

As Love dribbles off the pick from Omier, Maluach starts in drop coverage while James fights over the screen in pursuit. As Love dribbles near the arc, Maluach stays in the drop, but once the veteran guard drives closer to the paint, Maluach effectively switches onto him. Meanwhile, James breaks off his pursuit and sticks with Omier. Duke bottles this up perfectly; as Love dribbles under the rim and back up the lane, Maluach and James switch back to their original assignments. That’s outstanding defense, and the possession ends with a tough, contested off-dribble two-point attempt late in the shot clock.

Another adjustment from Duke was having its on-ball defenders "weak" the ball screen. In this pick-and-roll coverage, the on-ball defender forces the ball handler away from the screen. For example, notice how Proctor positions his body between the screen from Omier and Edgecombe, Baylor’s most talented ball handler.

By jumping out and angling his body this way, Proctor forces Edgecombe to dribble away from the screen with his weaker left hand and into the presence of Maluach. The result, after a pass from Edgecombe, is a challenging swooping hook shot from Omier, contested by Maluach.

Baylor countered this approach by popping or short-rolling Omier to the middle of the floor. While Omier isn’t much of a shooter, he can make plays in space. However, to continue the on-court chess match, James was extremely active coming off the weak-side wing, providing help at the elbow and disrupting pocket passes to Omier. James created multiple deflections by positioning himself in this exact gap.

Despite the challenges, Baylor managed to score 1.12 points per possession in this game, which is respectable, especially against an elite defense. However, that efficiency is largely due to the fact that Duke forced only five turnovers, a tradeoff typical of a drop coverage approach — less pressure on the ball, fewer turnovers — and allowed 18 offensive rebounds.

Baylor actually had a lower 2-point shooting percent (39.5 2P%) than it did offensive rebound rate (40.9%), shooting under 40 percent on its 2-point attempts for the seventh time this season. With only modest success from beyond the arc (8-of-25 3PA), Baylor posted an effective shooting rate under 44 percent for just the sixth time. This lack of success has a lot to do with Duke closing down the rim and forcing Baylor to take tough 2-point shots. According to CBB Analytics, Baylor attempted only 14 field goals within 4.5 feet of the rim (20.6 percent of the team’s total field goal attempts).

(Shot charts courtesy of CBB Analytics)

Conversely, Baylor attempted 25 field goals from inside the paint but away from the rim — a less efficient shot that accounted for nearly 37 percent of the team’s total field goal attempts. The Bears made just 8-of-25 (32%) on those attempts. This is the space that Duke wanted to stuff Baylor into.

Pat on the back

There’s no way to fully replace the injured Maliq Brown. At 6-foot-9, Brown is one of the best defenders in the country on a per-possession basis — regardless of position. Among high-major players this season, he is one of only five with a defensive box plus-minus above 6.0, per Bart Torvik. His unique combination of hand speed, nimble feet high-level feel makes him a game-changer, whether switching out on ball screens, hard hedging or defending 5-out actions at the point of attack.

That said, Brown’s absence has opened the door for more opportunities for Ngongba. The freshman 5 from Virginia has stepped into the role with confidence, adding physicality and new dimensions to Duke, on both sides of the floor.

Ngongba and Brown’s skill sets diverge and converge in interesting ways. On offense, Ngongba provides a level of frontcourt playmaking — picking out cutters from the elbows and working as a handoff hub in the middle of the floor — that allows Duke to keep running its offense through the high post when Maluach sits, a staple of this team when Brown is in the lineup.

With Ngongba on the floor and Maluach and Brown off (275 minutes), Duke’s offense has assisted on 67.3 percent of its field goals (56.2 percent assist rate in the minutes without Ngongba on the court this season) and posted an assist-to-turnover ratio of 2-to-1, according to CBB Analytics. Plus, Ngongba (6-11, 250) has the low-post power game to provide Duke with a back-to-the-basket bruiser. That’s something that Maluach and Brown, as good as they are, don’t really offer. In fact, Duke’s best post-up targets this season have been Flagg attacking switches and Knueppel when matched against a smaller guard.

While Duke obviously needs Brown to hit its defensive ceiling, Ngongba has more than held his own on that end, too. Duke is +171 in those 275 minutes with Ngongba on and Brown and Maluach on the bench, with a defensive rating of 98.5 points allowed per 100 possessions. Led by Ngongba, the Blue Devils have a dominant defensive rebound rate of 81.5 percent in those minutes, per CBB Analytics. Since the start of the ACC Tournament, Duke is +47 in 76 minutes with Ngongba on the floor, including a defensive rebound rate of 77 percent.

Late in the first half, Baylor runs spread pick-and-roll for Edgecombe, which Proctor again weaks — pushing Edgecombe to his left with Ngongba waiting in drop coverage. As Edgecombe attacks, Ngongba is able to move his feet, beat him to the spot and close off a direct line to the rim against one of the most explosive prospects in the future 2025 NBA Draft class. Edgecombe is forced to pick up his dribble and pass the ball out, with Ngongba following him to the 3-point arc. As Love tries to drive on Flagg, Ngongba is in the gap, digging down to help at the nail. Love kicks the ball back to Edgecombe and Ngongba makes another effort — again beating the talented guard to the spot and cutting off a lane to the hoop.

Given where Ngongba was a year ago, missing significant time with an injury, his current level of mobility is highly encouraging. It’s also a testament to both Ngongba’s work ethic and Duke’s sports science team. At this point, it’s almost commonplace to mention, but Ngongba is clearly a star in the making.

When Ngongba has shared the floor with Flagg during non-Maluach, non-Brown stretches, Duke is +128 in 133 minutes, with an offensive rating of 140.7 points per 100 possessions and a defensive rating of 82.3 points per 100 possessions.

Ngongba has tremendous hands and footwork, which he consistently utilizes on offense — isolating in the post, catching passes in traffic on the short roll and mashing on the offensive glass. He also puts those same tools to work on defense. Occasionally, while in drop coverage, he’ll surprise a ball handler by poking the ball loose with his reach and quick hands.

The freshman is also more than willing to get his hands dirty, mixing it up with a physical style of play in the paint and sacrificing his body to collect loose balls.

Secondary Effect

With Duke’s defense focused on limiting Baylor’s rim and roll options, the Blue Devils recorded only three steals in this game. However, Duke was highly opportunistic in its secondary offense, capitalizing on both missed and made shots. According to CBB Analytics, the Blue Devils scored 17 fast-break points, accounting for 19.1 percent of their total points.

The secondary attack clicked in this game as Baylor’s transition defense struggled to keep up with Duke’s speed and shooting. The Blue Devils took advantage with trail action, rim runs, staggered screens and hit-ahead passes to shooters.

Duke runs the floor will a purpose and a commitment to spacing. When Flagg drives the ball downhill, he knows where his shooters will be located — one in each corner, with another weak-side shooter spaced to the wing. When help defenders arrive, this allows Flagg, an already snappy decision-maker, to play with even more confidence. It removes any potential guess work. Independent of system, Flagg constantly makes good reads with the ball, delivering timely and accurate kick-out passes. That said, Duke’s system allows him to maximize his special traits.

One of Duke’s go-to quick-hitters in its secondary offense is Flagg as a trail man. James or one of the other guards will race up the floor with the ball on one wing while Flagg trails a step or two behind along the opposite wing. The other guards/wings fill the corners and the 5 runs the rim, which flattens out the defense and maintains balance for kick-out opportunities.

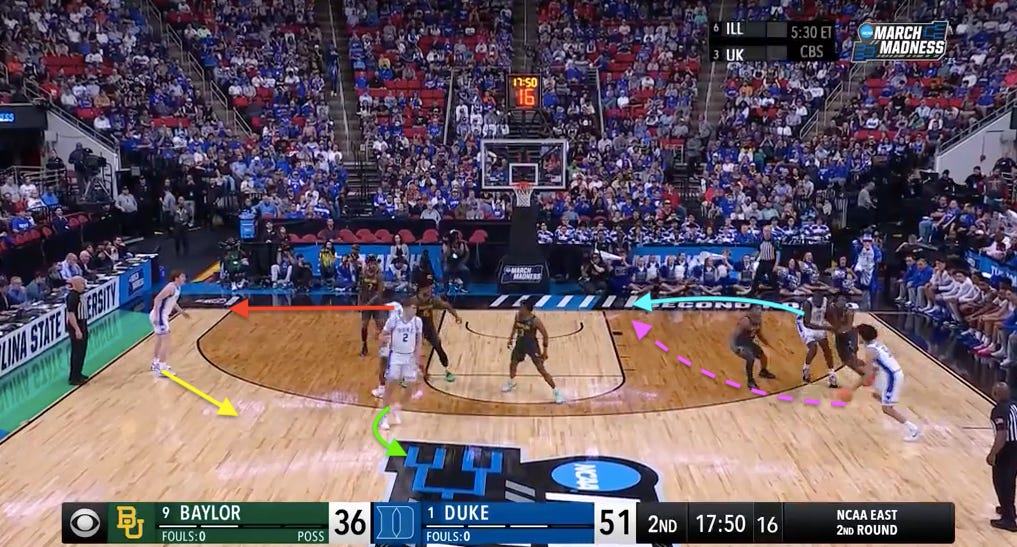

This secondary possession follows a Baylor field goal, but Duke is quickly off and running. James pushes the ball up the left flank, while Flagg trails on the right. Gillis and Proctor fill the corners, and Ngongba runs to the rim. Baylor’s transition defense is poor here, as there’s no (or not enough) communication about who has Flagg until it’s too late. James kicks it to Cooper, and Edgecombe scrambles to recover, allowing Flagg to get a closeout and attack.

From earlier in the first half: this secondary possession follows another Baylor make. Flagg passes the ball to Caleb Foster, and the two take off. Foster drives up the left side, with Flagg trailing on the right. With two top-notch shooters — Knueppel and Isaiah Evans — filling the corners, it puts immense pressure on the transition defense. Once again, the pace and space proves too much, and Baylor’s communication is lacking. Omier lets Ngongba run right by him, which Foster notices and responds to with a low, line-drive pass. Ngongba showcases his hands once again, gathering the ball from around his ankles and scoring at the rim.

Beyond his smooth processing abilities, Flagg is a physical force in the open floor. With his speed, long strides, decision-making and finishing skills — including a relentless determination to get to the rim — he’s a crisis for any defense in scramble mode.

This was Duke’s first bucket of the game: Knueppel grabs the rebound, takes one dribble and hits ahead to Flagg, who one-touch skip passes to a streaking Proctor on the opposite wing, resulting in a wide-open catch-and-shoot 3-pointer.

Flagg is also a terrific defensive rebounder and has the green light to grab and go. When he pushes the ball, the priority is the rim, but as the defense collapses toward the paint, it can open up kick-out opportunities for 3-pointers. Over 89 percent of Duke’s 3-pointers this season have been assisted (84th percentile). No one on Duke’s roster has assisted more 3-pointers than Flagg: 78, which accounts for half of his 142 total assists (54.9 percent). James is the next closest player, assisting on 53 3-pointers.

Foster does a nice job on this possession. Instead of stopping on the left wing with Knueppel landing in the corner, Foster cuts through. This movement causes indecision in Baylor’s transition defense: Edgecombe and Wright get caught in no-man’s land as Flagg snaps a pass to Knueppel for a spot-up 3.

A good counter against a switching defense like Baylor is the fake dribble-handoff (DHO). This tactic is also known as a “keep” move and it works almost like a would-be screener slipping a screen against a switch defense. The player with the ball will dribble in the direction of a teammate and position their body and handle as if they plan to hand it off to another in-motion player.

On this transition possession, Flagg dribbles up the left side of the floor, with Proctor to his left. Instead of filling deeper to the corner or cutting backdoor, Proctor moves toward Flagg — setting up the potential for a DHO between the two.

If two switching defenders see a DHO coming, they’ll load up and try to anticipate their new assignments — including whether or not they’ll end up with the ball. In this case, Wright expects to switch onto Flagg, while Edgecombe will shift to Proctor. However, the assumption is that Proctor will have the ball after receiving the DHO. Instead, Flagg keeps the ball, fakes the handoff and catches Wright by surprise, leading to a downhill drive and a foul.

Duke used these secondary possessions to quickly flow into different off-ball and 5-out actions. With the game tied at 21, James races up the floor as Foster fills the left corner. Instead of Maluach sprinting the rim and Mason Gillis looking for a catch-and-shoot 3 as a trail man, the two bigs set staggered down screens on the left side of the floor for Foster.

I refer to this as Duke’s “Strong” action. When Knueppel and Evans come off these staggered screens, they’re looking to shoot off the catch or curl and get downhill on a drive.

Foster, however, wants to use the advantage created by the staggered screens to set up his dribble drive. Baylor switches the staggered screens: Omier takes Foster and Edgecombe lands on Maluach. Normally, Maluach isn’t much of a post-up target, but with his size difference over the shorter Edgecome and no real secondary shot blockers on the floor, the 7-foot-2 Maluach seals in the lane and draws a foul.

Ngongba is the last man down the floor on this secondary possession. Instead of having him run to the rim, Gillis centers the ball to Ngongba as the trailer in the middle of the floor. Duke is perfectly positioned to initiate its 5-out Zoom action — a down screen into a handoff. James sets the down screen for Flagg, who lifts into the handoff with Ngongba. Meanwhile, Baylor is scrambling to set its half-court defense. The Bears seem to be trying to shift into a zone, but as Ngongba screens for Flagg, there’s no help defender to assist when Flagg dribbles off the pick, resulting in a lightly contested pull-up 3-pointer.

The Blue Devils also got to what I refer to as their “77 Veer” action in early offense against Baylor. To start, James will dribble right across the double drag ball screens (“77”) from Flagg and Maluach. After Flagg and Maluach set the double drag action, they clear to the left side of the floor and look ready to set staggered down screens for Knueppel coming out of the left corner.

Flagg’s movement here is simply to set up the next phase of the action. He’s not going to screen for Knueppel; instead, Maluach will screen for Flagg. Maluach slips his ball screen for James, and — with Omier, his defender, focused on James — he hits Flagg’s defender, Celestine, with a "Veer" down screen.

Flagg will curl around Maluach’s down screen and get a wide-open catch-and-shoot 3-point attempt. You can see Roach’s frustration with his teammates blowing the coverage.

During the late stages of the Clemson game last month, Duke went to the same action — with Brown as the other big man screener, working in tandem with Flagg. While the initial screening action doesn’t hit, Brown races back up and sets a step-up ball screen for Flagg. Clemson’s Ian Schieffelin and Viktor Lakhin get caught between a switch and drop coverage, allowing Flagg to walk into a pull-up 3.

Finding the matchup

For the first time in a while, Duke ran its continuity ball screen offense out of its Iverson series to attack Baylor’s 1-5 switch scheme. Continuity ball screen is a side-to-side motion-based pick-and-roll offense that operates as a series of continuous wing/empty-side ball screens.

First, to get into the action, the Blue Devils start by having Proctor run left-to-right across the formation, over two screens at the elbows from Maluach and Flagg, while Knueppel cuts left-to-right underneath the formation. This is the Iverson setup. As Proctor clears to the wing, James will pass him the ball and then cut through to the left corner. While that takes place, Duke will run screen-the-screen pick-and-roll action: Flagg screens for Maluach along the foul line, which draws a switch, putting the 6-foot-5 Love on Maluach, and lifts up to the left slot. Maluach exits Flagg’s screen with momentum and a slight advantage, running out to set an empty-corner pick for Proctor.

This is an excellent bit of screen-and-roll movement from Maluach, who makes contact with Wright and spins on his inside foot — opening up his body to the middle of the floor and creating inside leverage with the switch. He effectively seals his body between Wright and the rim.

Proctor could look to reverse the ball to Flagg in the opposite slot, which would trigger second-side pick-and-roll action, thus creating the action’s continuous side-to-side motion. However, with the defense lifted and Maluach having a clean pathway to the rim, Proctor makes the correct decision and hits his center for a rim-running dunk.

Earlier in the game, Duke went to this same action after the first media timeout. Knueppel and Ngongba run the empty-side ball screen action, but as Ngongba screens, spins and dives, he’s unable to get a clean line to the rim — mostly because Celestine grabs him with two hands like an offensive lineman in football. Regardless, the possession builds. Knueppel swings to Flagg, who reverses the ball to the right. James cuts through from the wing to the left corner and Proctor lifts up. As soon as Flagg kicks to Proctor, he follows the ball and sprints over to set a ball screen for Proctor. Before Flagg plants himself for the pick, though, Proctor decides to let it fly over a closeout from Roach.

Later in the second half, it’s the same action: Proctors cuts across the Iverson screens, Flagg screens for Ngongba (Omier switches to Flagg) and Ngongba runs out to screen on the ball. Initially, Proctor rejects the screen and drives right — before crossing over and coming back left over the screen. Proctor kicks to Flagg and that kickstarts the play’s second-side action. Knueppel cuts from the left wing to the opposite corner and Foster lifts up. Duke looks set to run a second ball screen with Foster and Flagg, but Flagg keeps the ball — faking another DHO. With Omier in foul trouble, Flagg’s DHO “keep” allows him to split a potential switch between Wright and Omier. Flagg misses the driving layup, but with his second jump, he’s able to draw a foul on the put-back attempt.

Duke scrambled the matchups with another set out of its Iverson series, designed to get Flagg attacking Omier in the middle of the floor. Proctor cuts left across the Iverson screen from Maluach and Knueppel, while Flagg drops from the left wing to the short corner. Once Proctor clears, Maluach sets another screen — this time popping Knueppel to the left wing, drawing a switch with Omier. Edgecombe switches onto Maluach. After screening for Knueppel, Maluach sets a down screen for Flagg, bringing him to the top of the key with Edgecombe switched onto him. With Omier now on Knueppel and Edgecombe on Flagg, Duke runs an inverted pick-and-roll: Knueppel screens for Flagg, creating another switch. Now, Flagg (5.7 fouls drawn per 40 minutes this season) is in a prime position to go after Omier, Baylor’s most important on-off player.

Flagg is difficult to stop 1-on-1, but he becomes even more of a challenge when the defender is trying to contain him while avoiding fouls.

Drew and Baylor continued to throw stuff at the wall, hoping something would stick — to no avail. The Bears tried to mix up their pick-and-roll coverages and went away from switching 1-5 on some possessions — opting to keep Omier a step or two below the level of the of the screen and then sink further into the paint. This type of coverage can be very effective and Omier has the mobility to guard in space, but he’s undersized for a center, plus Baylor doesn’t really have much length along the frontline. It’s hard to navigate this coverage without the necessary size around the paint.

(Remember: when Omier was at Miami, the Hurricanes used to hedge and blitz ball screens with Omier as their primary screen defender, an effort to lean into their speed and downplay their lack of size.)

Moreover, this type of defense isn’t Baylor’s base coverage. All of a sudden, in the middle of a game, guys are being asked to play in different spots and handle rotations. That can be difficult even when a defense has the time to prepare and a lot of reps. Trying to flip this switch against an offensive avalanche from Duke was Baylor grasping for straws.

For instance, Duke starts this sideline out-of-bounds play in a Box set: Knueppel inbounds the ball, Maluach screens for Flagg, who cuts from the left elbow out to the opposite wing and receives a pass from Knueppel. Flagg immediately flips the ball back to Knueppel, which creates a switch. The next part of the play features Knueppel coming out of the handoff action with Flagg and into a middle ball screen from Maluach. Omier meets Knueppel on the other side of the screen, but he doesn’t switch — he’s a step below the level.

Omier stays close to Knueppel as Celestine tries to fight over the screen. However, as Maluach rolls, Omier doesn’t sink fast enough, leaving Knueppel with essentially two defenders on the ball. When Knueppel faces two defenders in the pick-and-roll and there’s no tag on Maluach — which is what happens here with Nunn, focused on Flagg, letting him roll right by — it’s an automatic lob.

Keep in mind: Baylor’s low-man/weak-side rim protection on this play is the 6-foot-1 Roach. Given the size disparity, there’s likely not much that Roach could do here; however, dips just one toe in the lane, offers no resistance to Maluach and it’s go time above the rim.

A few minutes later, with Proctor breathing fire, Duke comes out in its staggered screen (“Strong”) set. Proctor starts in the left corner and races up the pindowns from Gillis and Maluach. James swings the ball to Proctor and that triggers a step-up screen from Maluach. Once again, as Proctor dribbles left off the pick, Omier is there to meet the ball handler. It’s not a switch, though. Omier sticks with Proctor for only a dribble or two. (Also, notice how the weak-side defenders tag and crash on Maluach on this play.) As soon as he starts to backpedal and retreat, Proctor has the space he needs to let it fly.

For the most part, Baylor has this contained pretty well, but this type of shot-making from Proctor is a coverage-beater. Proctor throws Baylor’s scheme right over the top rope.

The junior from Australia was special in the opening weekend of the NCAA Tournament, scoring 44 points on a combined 19 field goal attempts — with only two free throw attempts. Dating back to the start of the ACC Tournament, Proctor has hit 17-of-35 3-point attempts (48.6 3P%) from above the break, including 6-of-7 3-point attempts from the left wing. Currently, Proctor is one of 13 high-major players shooting 40 percent on 3-pointers (100+ 3PA) and 50 percent from inside the arc (100+ 2PA), along with Michigan State’s Jase Richardson and Chase Hunter of Clemson.

According to CBB Analytics, Proctor has shot 39 percent on “deep” 3-pointers this season — attempts from 25+ feet — which ranks in the 77th percentile nationally. While Proctor does most of his damage from deep off the catch (82.6 percent of his 3-pointers this season have been assisted), it’s notable that Duke has a couple of guys — Proctor, Flagg, Knueppel — who are capable of launching from beyond the arc out of isolation or the pick-and-roll.

Clear Out

Duke picked at a variety of different post-switch matchups against Baylor; it wasn’t just Omier. The Blue Devils also attacked the guard-guard switches of Baylor’s defense with their Horns “Clear” set play.

The action begins with a Horns set: two shooters in the corners — Gillis and James — and two players at the elbows: Proctor and Maluach. As Foster initiates, Proctor positions himself as if he intends to set a guard-guard screen with Foster to start the play. In theory, Baylor would switch this action: Love would take Foster, and Edgecombe would switch to Proctor, keeping the ball in front. However, just before making contact with the screen, Proctor slips and cuts to the left wing — off a flare screen from Maluach.

Edgecombe is prepared to switch, but since Proctor doesn't actually set the screen, Love stays with him, which compromises Baylor’s defense. As a result, Edgecombe is out of position at the point of attack, and Foster takes advantage with a quick-strike drive. This is a smart play for Foster, as it allows him to do what he does best: attack a tilted defense with good pace.

The last time Duke played a team that switched 1-5 it was the penultimate home game of the season: Florida State back on March 1. According to my own charting, Duke ran this set five times in that game, scoring multiple times and drawing multiple fouls.

Here, the Blue Devils run Horns Clear against FSU, with the game already out of hand in the second half. Foster initiates the play, and Evans runs the ghost/blur screen, slipping from the right elbow to the left wing. FSU switches the action, but the switch is far from smooth, causing confusion at the point of attack. Foster takes advantage, turning the corner and kicking it to Flagg in the left corner. This creates a catch-and-go opportunity, which leads to another kick-out — this time to a relocating Evans.

This is an action that Duke’s had in its playbook for a long time now, too. In fact, here’s Tre Jones running Horns Clear during a 2019 game against Central Arkansas.

Slice it up

Finally, Duke created two buckets off of what I like to call its “Slice” series.

To start, the Blue Devils position themselves with the same staggered screen setup on the wide side of the floor. However, instead of Proctor running out of the right corner and using the staggered down screens from Foster and Ngongba, Duke splits the action: Proctor cuts toward the middle of the lane, Foster moves to the near-side wing and Ngongba lifts to the right slot, where he receives a pass from Flagg.

As soon as Flagg swings the ball to Ngongba, he cuts across the lane and off a slice screen from Proctor. This slice screen will either allow Flagg to carve out deep post position or get a smaller defender switched on him in the post, which is what happens here — Edgecombe switches from Proctor to Flagg. After screening for Flagg, Duke gets into its screen-the-screener action, looking for a 3-ball: Proctor quickly sprints off a down screen in the middle of the floor from Ngongba.

Love trails behind Proctor after the initial switch and there isn’t a second switch with Omier, which leaves Love on an island, chasing the hottest shooter in the builder. The result is an open catch-and-shoot 3 for Proctor.

Midway through the second half, Duke went back to this same set — now with Knueppel running the screen-the-screener action. Knueppel sets the slice screen for Flagg and then comes off the down screen from Maluach, which Baylor switches this time. Now, Knueppel has Baylor’s center, who is dealing with foul trouble, in his sights. Knueppel drives left and turns the corner on Omier, who doesn’t want to engage too seriously and pick up another foul.

This looks very similar to what Duke ran multiple times against UNC in the ACC Tournament semifinals — with Knueppel in Flagg’s role. Here, Proctor slices Knueppel to the strong-side block and then comes off the middle down screen from Maluach. Seth Trimble chases hard and denies the quick catch-and-shoot 3-pointer. Proctor counters with a pass to Maluach at the elbow, which initiates a quick give-and-go pick-and-roll. As Proctor turns the corner, Ven-Allen Lubin is caught off his line in drop coverage and it’s a lob over the top to Maluach.

Sweeten the deal

Making it to the Sweet 16 is a terrific accomplishment for this team, but the pressure ramps up from here. As Duke travels to Newark for the rematch with Arizona, it’ll mark the first time the team has left the state of North Carolina since a road date at Miami back on Feb. 25. The Wildcats have size, speed along the perimeter and a 3-and-D wing in Carter Bryant (6-8, 235) who can matchup with Flagg, plus stretch-5 Henri Veesaar (32.7 3P% and 11.8% assist rate) has improved throughout the season. Veesaar is a matchup concern for any opponent.

The specter of Caleb Love hangs over head, too. Love has always been a high-variance player, as one might expect with a creator whose shot diet relies so heavily on deep, off-dribble 3-pointers. Going back to the 2007-08 season, Love is one of only three high-major players — along with Max Abmas and Jordan Bohannon — to attempt over 1,100 3-pointers. While Abmas and Bohannon each finished their extended college careers shooting above 38.5 percent from deep, Love is under 33 percent for his career. Of course, Love can get hot from beyond the arc, and when the happens it opens up his drive game and alters the geometry of Arizona’s half-court offense.

Buckle up. It’s nothing but nets from here on out.